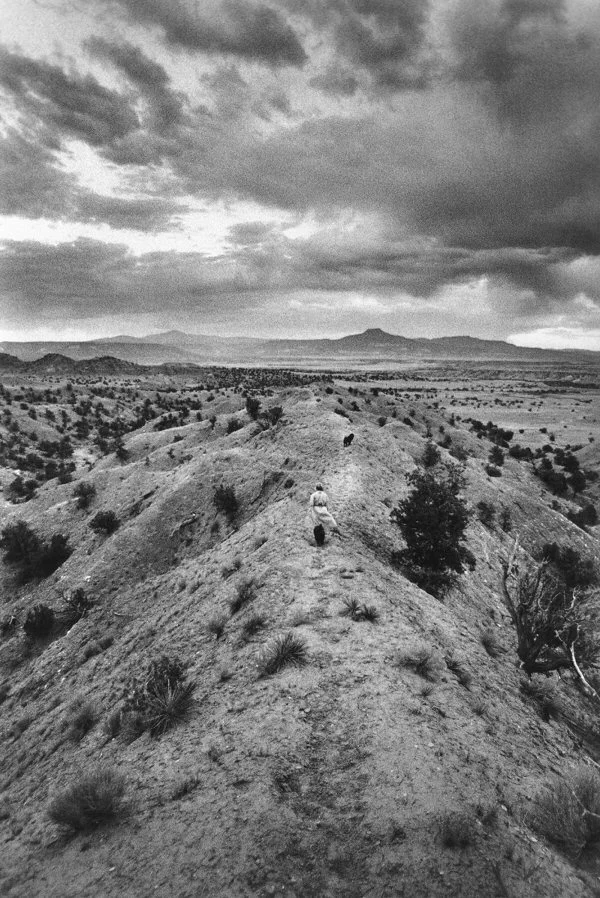

the LAND and the Sacred Face of Pedernal

Georgia O'Keeffe, often celebrated as the Mother of American Modernism, found her truest muse in the elemental vastness of northern New Mexico. Of all its sculptural peaks and sun-drenched mesas, none captured her heart more wholly than Pedernal—known to the Tewa people as Tsi Ping. For O’Keeffe, this flat-topped mountain was more than a subject; it was a spiritual lodestar, a presence she painted obsessively and claimed in spirit. “God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it,” she once mused.

Today, nestled directly beneath the very face she longed for, the LAND holds a vantage unlike any other—a full, frontal view of Pedernal’s wide-browed silhouette, as if the mountain were meeting you eye to eye. It is the closest, most direct alignment to the sacred mesa. This is the angle O’Keeffe spent a lifetime chasing—an angle we now call home.

The Sacred Geometry of Place

Set in the high desert of Abiquiú, the LAND is positioned in an alignment of uncanny elegance. This is not merely a view—it is a meeting. Here, the mountain does not sit off to the side or drift along a horizon. It rises, fully and frontally, anchoring the sky like a living sculpture. The effect is profound: heart rates slow, the nervous system exhales, and a quiet sense of creative urgency begins to stir. O’Keeffe knew this sensation. It animated her palette and shaped her vision.

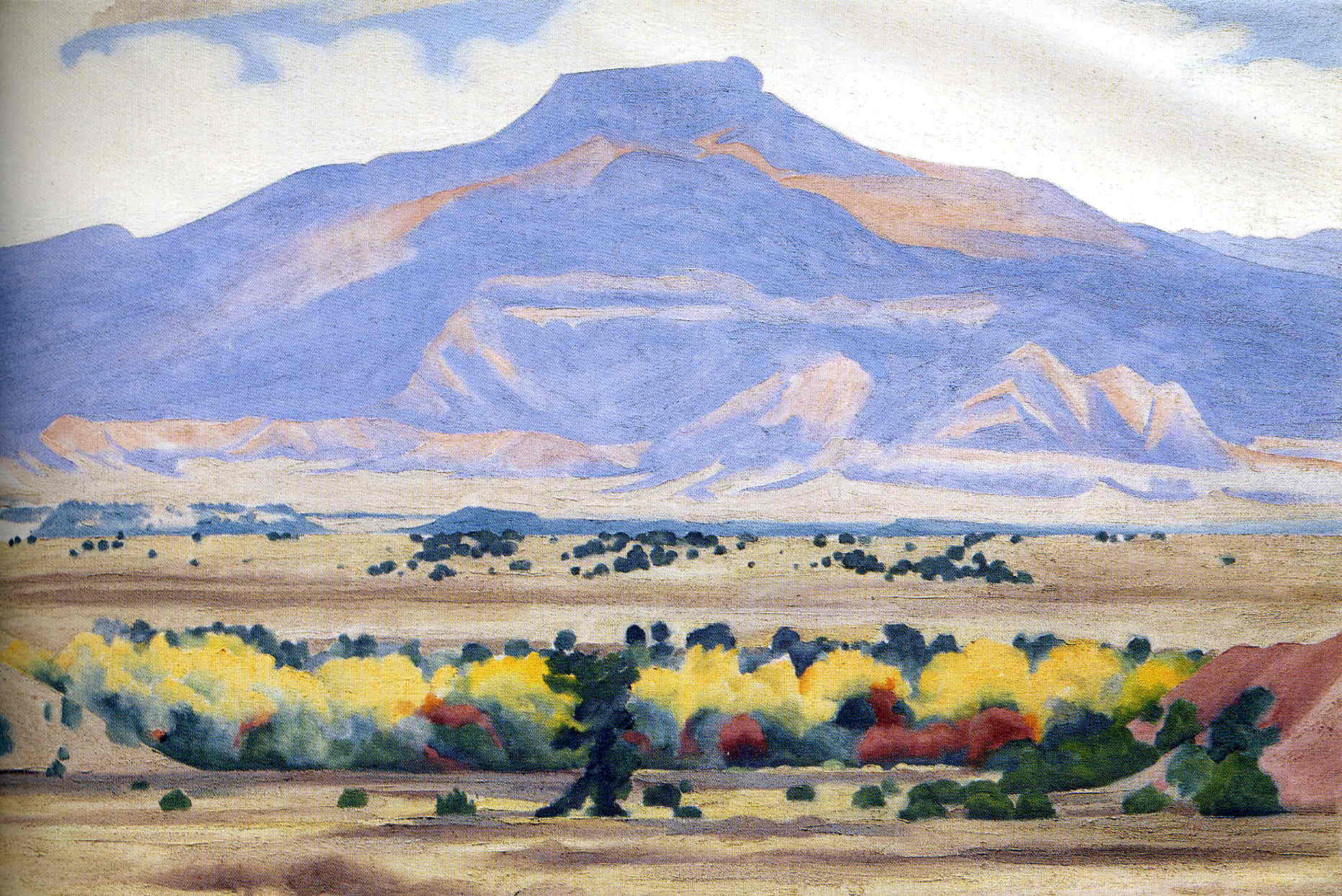

The Pedernal in O’Keeffe’s Gaze

In canvas after canvas, O’Keeffe returned to the mesa. Sometimes softened in haze, other times silhouetted against brilliant azure, Pedernal became her anchor—her altar. The painting Pedernal, 1941–1942 renders it in deep cerulean blues, a monolith of quiet resolve. In Deer’s Skull with Pedernal, the mountain hovers behind bone—a dialogue between death and permanence, between spirit and form. But no matter the interpretation, one truth remains: she never tired of painting it.

What she never quite captured, however, is what the LAND now holds—this perfect angle. It is the living answer to her lifelong desire.

Where Spirit and Stone Intertwine

To O’Keeffe, Pedernal was not just geological. It was devotional. It offered solitude, a stillness that mirrored her own contemplative nature. It was this sacred stillness that drew her back again and again, and it was here—on the summit—that her ashes were scattered, returned to the very form she called hers.

From the LAND, it feels as though she never left. The air still trembles with the quiet intensity she sought. The light still pours across the valley in brushstrokes. The mountain still watches.

Honoring Tsi Ping

Yet long before O’Keeffe’s arrival, the Tewa people recognized this place as holy. Tsi Ping is not merely a landmark—it is a living being, a story-bearing elder. Its form is part of ceremony, its silhouette etched into memory and song. To live beneath it is to dwell within a lineage of reverence. At the LAND, we honor this truth. We do not claim the mountain. We listen to it.

The Legacy Endures

Today, Pedernal still presides over this northern corner of the earth with quiet majesty. And the LAND, cradled at its feet, becomes more than a retreat or a destination—it becomes a threshold. A place to remember what it means to see clearly, to create with reverence, to live in rhythm with the land and sky.

O’Keeffe dreamed of this view. We are merely its current stewards.

.svg)