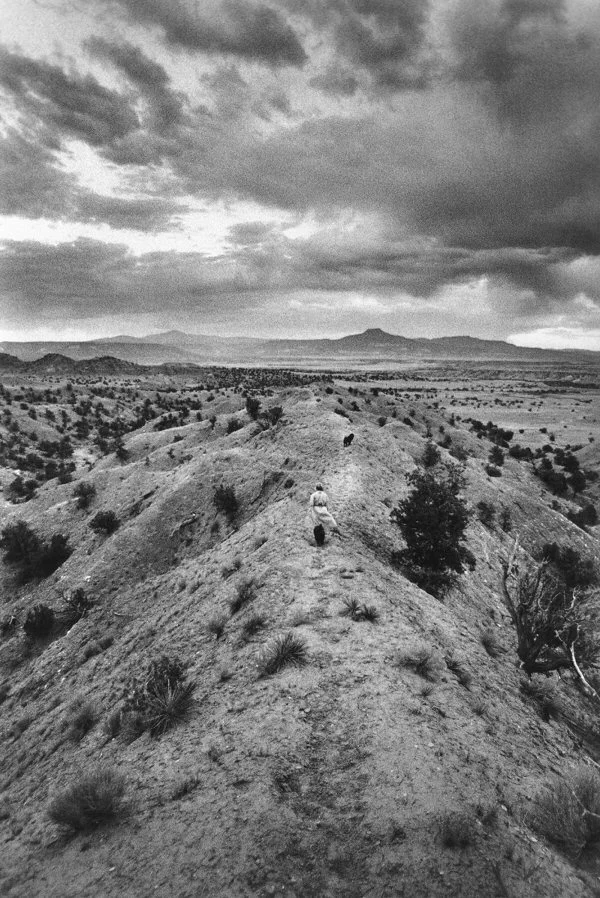

Some people ask, “What’s the story of that incredible mountain?”

To which we reply: “Where do you want to start the story?”

Because the mountain known today as Cerro Pedernal—or more truly, Tsi Ping—is not just a landmark. It is a palimpsest of memory, a sacred being, a site of resistance, and a mirror reflecting the layered histories of this land.

Tsi Ping: The Sacred Mountain of the Tewa

Long before Georgia O’Keeffe painted its silhouette, the Tewa people revered this mountain as Tsi Ping, meaning “Flint Mountain” or “Flaking Stone Mountain.” This name reflects both the geological presence of chert and the mountain's spiritual significance. Nearby, the ancestral Tewa village of Tsi’pin-owinge—translating to “Village at Flaking Stone Mountain”—was occupied between 1275 and 1450 AD. This site, perched atop a mesa at 7,400 feet, once housed approximately 1,000 inhabitants and featured 16 kivas, including a Great Kiva carved into the volcanic tuff of the mesa itself.

For the Tewa, Tsi Ping is not merely a physical landmark but a living entity, a relative, and a guide. It is a being whose presence is integral to their cosmology and cultural identity.

The Spanish Colonial Legacy: Naming and Claiming

The arrival of Spanish colonizers in the 16th century marked a significant shift in the narrative of Tsi Ping. The mountain was renamed Cerro Pedernal, translating to “Flint Hill,” a nod to the chert found in its cliffs. This act of renaming was part of a broader colonial strategy to assert control over the land and its resources.

In 1598, Don Juan de Oñate declared Spanish sovereignty over the territories north of the Rio Grande through a proclamation known as La Toma. This event marked the beginning of a period characterized by the establishment of missions, forced conversions, and the suppression of Indigenous cultures. The Spanish missions in New Mexico were a series of religious outposts aimed at converting Native Americans to Christianity and facilitating the colonization process.

The renaming of Tsi Ping to Cerro Pedernal exemplifies the colonial practice of erasing Indigenous identities and imposing new narratives upon sacred landscapes.

Georgia O’Keeffe and the Artistic Reimagining

In the 20th century, artist Georgia O’Keeffe became enamored with the mountain, frequently depicting it in her paintings. She once claimed, “It belongs to me. God told me if I painted it enough, I could have it.” While her artistic contributions brought global attention to the region's beauty, they also contributed to a narrative that often overlooked the mountain's deeper cultural and spiritual significance.

O’Keeffe’s works, while iconic, represent a reimagining of the landscape through a Western lens, one that often fails to acknowledge the mountain's sacred status among Indigenous communities.

A Call for Decolonized Engagement

To truly honor Tsi Ping, we must engage with it through a decolonized perspective—recognizing and respecting its significance to the Tewa and other Indigenous peoples. This involves acknowledging the mountain's original name, understanding its role in Indigenous cosmologies, and resisting narratives that seek to appropriate or commodify sacred spaces.

As visitors to the LAND, we are invited to look beyond the aesthetic allure of Pedernal and engage with its profound cultural and spiritual dimensions. This means listening to the stories of the Tewa and Diné peoples, respecting sacred sites, and recognizing the mountain as a living testament to a rich tapestry of histories and beliefs.

An Invitation: Embrace the Original Name

Next time you gaze upon the majestic silhouette of this mountain, consider referring to it by its original name: Tsi Ping. In doing so, you honor the enduring presence and wisdom of the Indigenous communities for whom this mountain has always been sacred.

Let us not just admire the beauty of the landscape but also commit to understanding and respecting the deep-rooted histories and cultures that have shaped it.

For those seeking to explore this sacred landscape, please approach with respect and mindfulness, acknowledging the deep-rooted significance it holds for the Tewa and Diné peoples.

Note: This article draws upon various sources to provide a comprehensive understanding of Tsi Ping/Cerro Pedernal's cultural and historical significance.

.svg)